Body Condition Scoring: Keeping Your Horse Healthy One Number at a Time

By Christine Rudd, MSc, CTRI

“What’s his body condition?” your vet asks you over the phone.

“He’s a little on the skinny side, but not too bad,” you answer.

What does “a little on the skinny side” mean? What does chubby, fit, or fat look like? The simplest and least satisfying answer is, it depends on who you ask. To a racehorse trainer a champion hunter might look fat, while a western pleasure competitor might think event horses are too skinny. However, for each horse’s job and body type, they might be healthy and fit.

To avoid subjective descriptions of equine body condition, an objective and standardized body scoring system is necessary. This system is not only for veterinarians and owners to accurately describe a horse, but also to enable law enforcement professionals to describe animals encountered on welfare calls, and equine industry professionals from diverse backgrounds to describe a horse’s physique in a common language.

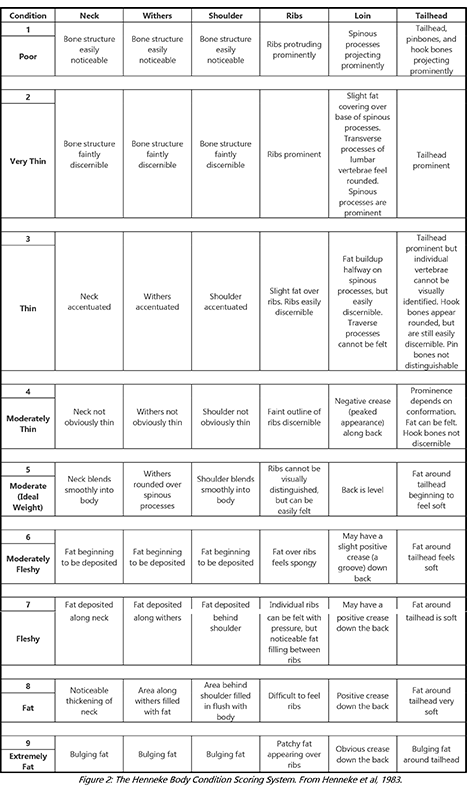

Body scoring systems rank a horse’s condition on a numeric scale, with each score directly connected to a rigid set of observable and palpable characteristics. These characteristics are descriptions of fat and muscle cover over key body areas (Shuffitt & TenBroeck, 2003).

There have been two main body scoring systems used in the horse industry: the Leighton-Hardman model developed in 1980 that ranked horses’ condition on a scale of 0-5, and the Henneke Body Condition Score (BCS), used more commonly today, that ranks a horse’s condition on a scale of 1-9. On both scales, the lowest number is reserved for the severely emaciated horse, the horse’s condition improves through the middle of the scale, then tips toward obesity as the higher scores are reached.

There have been two main body scoring systems used in the horse industry: the Leighton-Hardman model developed in 1980 that ranked horses’ condition on a scale of 0-5, and the Henneke Body Condition Score (BCS), used more commonly today, that ranks a horse’s condition on a scale of 1-9. On both scales, the lowest number is reserved for the severely emaciated horse, the horse’s condition improves through the middle of the scale, then tips toward obesity as the higher scores are reached.

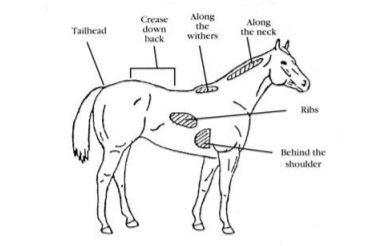

The more commonly used model, the Henneke Body Condition Score, was developed by Don Henneke, PhD. The Henneke scoring system is accepted in courts of law as a fair and objective system to score horses recovered in welfare and cruelty cases. It is based on six major points on the horse’s body where fat can be both observed and palpated: the neck, shoulder, withers, ribs, loin, and tailhead, and is applicable across all breeds and disciplines.

When determining the body score of a horse, it is important to not only look at the horse, but also to firmly run your hand over these key areas to feel the amount of fat and muscle cover. This gives you the opportunity to feel how much flesh there is between the skin and the ribs, how much of that fluff is hair and how much is fat, or to feel the lack of fat and muscle under a thick and concealing coat.

While this body scoring system is uniform across breeds and disciplines, there are a few exceptions to be aware of. These exceptions come mainly in the conformational differences between breeds, which can make certain criteria difficult to apply to each animal, so breed characteristics (such as differences in wither structure and prominence) should be taken into account when assessing body condition score. In pregnant mares, an emphasis is put on musculature and fat behind the shoulder, around the tailhead, and over the neck and withers, since the weight of the fetus can pull the skin taut over the back and ribs (Henneke et al., 1983).

Knowing your horse’s BCS is not only important so you can accurately communicate about your horse, but also so you can ensure your horse’s good health. A low body score can be indicative of a number of factors, such as nutritional requirements not being met, dental disease, parasite load, or sickness. On the other end of the scale, a higher body score can indicate certain diseases, be a causal factor of laminitis, as well as the health problems that come with excess amounts of body fat such as Equine Metabolic Syndrome and increased stress on joints and soft tissue (Shuffitt & TenBroeck, 2003; Jackson 2007). In growing horses, recognizing the signs of under- or over-nutrition can prevent or offset the health risks associated with said conditions (Staniar, 2004).

By using a standardized BCS to routinely evaluate your horse, you are taking the guess work out of home health maintenance. There is no “maybe” when it comes to whether your horse is over- or underweight, whether that divot over your horse’s spine is healthy (it’s not), or if your feeding program is adequately addressing your horse’s energy needs. It gives you a concrete tool to know when to call the vet or nutritionist based on changes in your horse’s body and you’ll be able to appropriately define and describe that change. As you practice your critical observation skills, the rosy veil of adoration that hides our horses’ less than healthy imperfections begins to lift, and we will become better owners and managers who can effectively advocate for and initiate feeding and exercise programs that will keep our horses in a healthy body condition. Being familiar with the Henneke BCS and regularly practicing it empowers you to understand and identify the good, the bad, and the ugly of equine body conditions, and with the help of your vet or other equine service provider, you can bring your horse back to that ideal 5.

For more information on body condition scoring, please reference the studies provided in the References section below.

References

Henneke, D. R., Potter, G. D., Kreider, J. L., & Yeates, B. F. (1983). Relationship between condition score, physical measurements and body fat percentage in mares. Equine veterinary journal, 15(4), 371-372.

Jackson, C. (2007). University researchers lead pioneering study in equine obesity.

Leighton-Hardman, A.C. 1980. Appendix 3. Weight estimation tables. Pages 106-107. In: Equine Nutrition. Pelham Books, London.

Shuffitt, J. M., & TenBroeck, S. H. 2003. Body Condition Scoring of Horses.

Staniar, W. B. (2004, March). Understanding Equine Growth. In CONFERENCE SPONSORS (p. 180).

Horse-Human Interactions and Equine Welfare in EAAT: Aligning Our Practices With Our Goals

PATH Intl. Equine Welfare Committee Guest Tip from Emily Kieson, PhD candidate at Oklahoma State University

The world of equine-assisted activities and therapies (EAAT) is saturated with activities and horse-human interactions based almost exclusively on the historical use of horses for work and equitation. The same routines of haltering, grooming, riding, leading and lungeing that have been used for years in equitation have been adapted by the EAAT world to serve new purposes, and professionals in EAAT consider the horse a partner. These interactions, useful for training and schooling our horses for use in work and pleasure, may not, however, be in line with the goals of therapy. (Editor’s note: PATH Intl. Certified Professionals do not practice therapy but rather equine-assisted activities. Those participants in need of therapy are served by licensed physical and occupational therapists, speech/language pathologists and mental health professionals.) Researchers are learning more about how domestic horses communicate with each other and us, which can lead to improvements in equine welfare through better understanding of equine-human interactions and what it means for the psychological welfare of the horse. This means that, if we want to improve client-horse relationships and model good horse-human relationships for our participants, we may need to make different choices with regards to how we handle or interact with our equine partners.

As humans, we explore the world through our hands and express emotional connection through touch [1], [2], words and sharing of food [3]–[5], whereas emerging research shows that horses create bonds through proximity [6], time and mutual engagement rather than touch or pressure. Based on recent (unpublished) studies, horses engage in social connection with other horses through close proximity and a sharing of quiet space repeatedly over time. Instead, they stand quietly near their favorite partner and share mutual space while resting or grazing. Perhaps even more importantly, the relationships they build with one another are based not only on predictably safe interactions, but also mutual exploration and partnership in problem solving. Once a safe space has been established between two horses, they will begin moving and exploring together. Everything is mutual with no single leader or follower and even touch is always simultaneously reciprocated. One may demonstrate more confidence than the other, but there is no pushing or pulling to force engagement of the partner, just an invitation to join in curiosity and exploration. The joint involvement in uncertain environments is what makes horses build better relationships.

The same is true for humans, too. We build safe environments with each other over time in order to build trust and, once that trust is established, a relationship is strengthened by small challenges and uncertainties that are explored as a team [7]–[10] . These concepts have been supported by scientists who study marriage, families, friendships and work partnerships and have been studied in a wide range of species. It appears these same concepts apply to horses as well.

So how do we incorporate this into EAAT and what does this mean for welfare? Traditional equitation relies almost exclusively upon negative reinforcement (pressure and release) [11]–[13] which, when properly used, can adequately train a horse to engage in a behavior of our choosing. This use of small aversive tactics, however, does not align with how either species builds relationships. If we are hoping to work with horses in a way that both encourages and models balanced partnerships, perhaps we need to incorporate other types of interactions into our EAAT programs. This may mean, then, that we do not always ride or halter a horse and that the horse may have a choice to not engage with the participant. This may require us to set different expectations for participants and parents and help them understand why we are encouraging at-liberty work and what that means for building mutual communication and engagement for both horse and human. Horses have amazing memories and build unique relationships with each individual human that can build and develop over time. If we give our horses the choice of engaging with clients in a way that better aligns with their natural behavior, perhaps we can improve the welfare of our equine partners while simultaneously finding even better ways to build confidence, communication and emotional strength in our clients.

[1] R. I. M. Dunbar, “The social role of touch in humans and primates: Behavioural function and neurobiological mechanisms,” Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 260–268, 2010.

[2] A. V. Jaeggi, E. De Groot, J. M. G. Stevens, and C. P. Van Schaik, “Mechanisms of reciprocity in primates: Testing for short-term contingency of grooming and food sharing in bonobos and chimpanzees,” Evol. Hum. Behav., 2013.

[3] J. Koh and P. Pliner, “The effects of degree of acquaintance, plate size, and sharing food intake,” Appetite, no. 52, pp. 595–602, 2009.

[4] A. N. Crittenden and D. A. Zes, “Food Sharing among Hadza Hunter-Gatherer Children,” PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 7, 2015.

[5] J. M. Koster and G. Leckie, “Food sharing networks in lowland Nicaragua: An application of the social relations model to count data,” Soc. Networks, 2014.

[6] M. C. Van Dierendonck, H. Sigurjónsdóttir, B. Colenbrander, and a. G. Thorhallsdóttir, “Differences in social behaviour between late pregnant, post-partum and barren mares in a herd of Icelandic horses,” Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., vol. 89, pp. 283–297, 2004.

[7] J. K. Rempel, J. G. Holmes, and M. P. Zanna, “Trust in Close Relationships,” J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 95–112, 1985.

[8] B. Vollan, “The difference between kinship and friendship: (Field-) experimental evidence on trust and punishment,” J. Socio. Econ., vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 14–25, 2011.

[9] R. J. Lewicki and B. B. Bunker, “Developing and Maintaining Trust in Work Relationships,” Trust Organ. Front. Theory Res., no. October, pp. 114–139, 2015.

[10] R. J. Lewicki and R. J. Bies, “Trust and Distrust : New Relationships and Realities,” vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 438–458, 2018.

[11] J. Murphy and S. Arkins, “Equine learning behaviour.,” Behav. Processes, vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Sep. 2007.

[12] P. D. McGreevy and A. N. McLean, “Punishment in horse-training and the concept of ethical equitation,” J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res., vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 193–197, Sep. 2009.

[13] A. N. McLean and J. W. Christensen, “The application of learning theory in horse training,” Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., vol. 190, 2017.

Additional Resources:

J.M. Gottman, The Science of Trust: Emotional Attunement for Couples. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. 2011

Feltman, The Thin Book of Trust. Bend, OR: Thin Book Publishing, 2008.

Rees, Horses in Company. London: J A Allen & Co Ltd. 2017

McGreevy, Equine Behavior: A Guide for Veterinarians and Equine Specialists 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2012.

McGreevy, A. McLean, Equitation Science. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010

About the author: Emily Kieson is a PhD candidate at Oklahoma State University in comparative psychology studying equine behavioral psychology and equine-human interactions. She has a M.S. in Psychology, a graduate degree in Equine Science, is certified and practices as an Equine Specialist in Mental Health and Learning through PATH, and is certified as an Equine Specialist in a number of other EAP models. She has spent the last 20 years working full time in the horse industry and has focused the last 10 years on equine-assisted therapies. Emily, along with her colleagues at MiMer Centre, a Swedish non-profit, are helping to develop a research and education center at OSU with a focus on animal-human interactions and animal welfare.